The Literary Legacy of the Vietnam War

More books have been written about the Vietnam war than about any other American war. The "official" version of the war lost credibility early and individuals had to make sense of it for themselves. A large number wrote books based on their experiences, many of which were published by small presses or by the authors themselves and received no distribution to speak of. Even books from large publishers came and went as if they were written on air. And tracking down the literature of Vietnam is doubly difficult because, in an era which declared the "novel" dead and saw the birth of the "new journalism," it is not easy to decide just what constitutes "literature" and what is simple history or mere reporting. Just as the Vietnam war stretched our definitions of warfare--with such memorable lines as "we had to destroy the town in order to save it"--the literature of the war wants its own categories, and falls uneasily into the standard ones.

That said, there clearly is a literature of the war, and enough of it that one can identify the good and the bad with some certainty. And there is a sizable body of very good literature about a war which, by most accounts, was a very bad war. It's as if the books have to be exceptional, in order to have a chance of measuring up to the task of outweighing or counterbalancing the war. Of the nobler examples of the human behavior, the Vietnam war of popular imagination provides little evidence. The country was so polarized about Vietnam that by the mid-Sixties putting any kind of positive spin on the war was seen as a reactionary political statement, no more credible than the daily military press briefings which came to be known as the Five O'Clock Follies.

It has taken a generation for the war to lose enough immediacy that it can be looked at with something of a cool eye, and discussed without raised voices--most of the time. Vietnam rended America as no war had since the Civil War, and the wounds are still tender. The literature of this war has the double task of revealing those wounds in the first place, as well as providing the vision and understanding to try to heal them.

A number of authors of high repute cut their literary teeth on

accounts of the war, both nonfiction and fiction. Robert

Stone covered it for an English magazine, and later wrote a

book, Dog Soldiers, which was set partly in Saigon and

partly in the U.S. and dealt with the pervasive sense of

individual and institutional corruption which Vietnam seemed

to embody--a society gone bad, with no meaningful redemption

except in the individual's code of honor, invented on the fly,

and ultimately capable, perhaps, of saving the indvidual, but

insufficient for a society in which the most extreme paranoia

seemed barely able to accomodate the tangled web of mistrust

and betrayal. In this context, the most astonishing behavior

could seem normal or rational, considering the circumstances,

and normal moral compasses had been discarded: individuals

were on their own. Dog Soldiers won the National Book

Award, the first literary work on the war to be so honored.

A number of authors of high repute cut their literary teeth on

accounts of the war, both nonfiction and fiction. Robert

Stone covered it for an English magazine, and later wrote a

book, Dog Soldiers, which was set partly in Saigon and

partly in the U.S. and dealt with the pervasive sense of

individual and institutional corruption which Vietnam seemed

to embody--a society gone bad, with no meaningful redemption

except in the individual's code of honor, invented on the fly,

and ultimately capable, perhaps, of saving the indvidual, but

insufficient for a society in which the most extreme paranoia

seemed barely able to accomodate the tangled web of mistrust

and betrayal. In this context, the most astonishing behavior

could seem normal or rational, considering the circumstances,

and normal moral compasses had been discarded: individuals

were on their own. Dog Soldiers won the National Book

Award, the first literary work on the war to be so honored.

Another author who has gone on to substantial literary acclaim

and is now widely collected covered the war from a different

perspective--that of a foot soldier, or "grunt." Tim

O'Brien's first book, If I Die in a Combat Zone, Box Me Up

and Ship Me Home was published in 1973 as American

involvement in the war was winding down. O'Brien conveyed the

conflicted sense that those who did go to war had--the idea

that serving one's country, in those times, in that war, could

be morally ambiguous. The book received excellent reviews,

went into second and third printings almost immediately, yet

is exceedingly uncommon today, even in the later printings.

The first printing, coming at a moment when virtually the

entire country was turning its back on the war, must have been

extremely small. A fine first edition these days sells for

$650 or more, and even at that price they are scarce: a

collector has to wait for one to appear rather than expect to

be able to purchase one as soon as the decision to go ahead

and spend the money is reached. O'Brien later won the

National Book Award for his third book, Going After

Cacciato, a surrealistic novel about a foot-soldier who

walks away from the war.

extremely small. A fine first edition these days sells for

$650 or more, and even at that price they are scarce: a

collector has to wait for one to appear rather than expect to

be able to purchase one as soon as the decision to go ahead

and spend the money is reached. O'Brien later won the

National Book Award for his third book, Going After

Cacciato, a surrealistic novel about a foot-soldier who

walks away from the war.

One of the scarcest and least-known Vietnam war novels is a book which for a long time was thought to perhaps be only a rumor. Ugly Rumours by Tobias Wolff was only published in England (George Allen & Unwin, 1975), and Wolff, who later won a PEN Faulkner prize for his novella The Barracks Thief, and whose memoir This Boy's Life was judged one of the best books of the year in 1989, has been less than forthcoming about Rumours' existence. It is not listed as a previous publication on his later books and it has not been reprinted. Wolff appears to wish to leave it behind him in permanent obscurity; in other words, it is a collector's delight. One of the joys of collecting is the "archivist's impulse"--the conviction that one's efforts serve the larger purpose of recognizing and preserving the worthy; while an author may dislike or even be embarrassed by an early work, a collector (or archivist) may legitimately judge that this is nonetheless worth preserving--that its worth is validated by the author's later accomplishments. While the author's judgements can be acknowledged and respected, the collector's are valid as well.

Wolff, Stone and O'Brien are probably the three best examples of authors whose Vietnam writing stands out above the crowd and who have also achieved a substantial degree of literary recognition, and therefore collectibility, outside the field of Vietnam literature. Within the field, however, are some extraordinary books which notably contribute to our literature and are works of art in their own right. Some are well-known, others obscure; what they have in common is that they attempt to capture an experience whose combination of a horrific physical reality with ambivalent moral dimensions strains the coolest description, even today.

The most well-known and universally acclaimed of these books

is Michael Herr's simply and aptly titled Dispatches.

Herr went to Vietnam on assignment from Rolling Stone

and Esquire, and it was he who popularized Vietnam as

the first rock'n'roll war; over several years he sent back a

series of riveting, absolutely unpredictable dispatches which

portrayed a war so completely different from the one the

politicians and generals were describing as to confirm forever

the "credibility gap" between what was happening in Vietnam

and what was being relayed to the American public about it.

and Esquire, and it was he who popularized Vietnam as

the first rock'n'roll war; over several years he sent back a

series of riveting, absolutely unpredictable dispatches which

portrayed a war so completely different from the one the

politicians and generals were describing as to confirm forever

the "credibility gap" between what was happening in Vietnam

and what was being relayed to the American public about it.

Dispatches collects Herr's pieces--"Hell Sucks" and "Illumination Rounds," for example--taking the slogans and jargon of the war and fashioning pieces which are picture-perfect in their clarity while being absolutely hallucinatory in their content. "Khe Sanh" is about the futile Marine defense of a besieged base in a far corner of Vietnam which was one day abandoned when it was no longer considered "strategic." Defended at astounding cost and with untold amounts of bravery, Khe Sanh came to symbolize the entire ill-conceived and ill-fated American involvement in Vietnam. Unlike the polemical reporting dominating the media during the war, Herr's reports didn't moralize much; they let the grunts do most of the talking, and it came out in a language as idiosyncratic and revealing as any specialists' anywhere would. These grunts spoke the language of survival amid unthinkable chaos, destruction, and torment. Their words came like a piercing beacon from the other side of the "thousand-yard stare" so prevalent among the prematurely aged young fighters. Herr's book contains some of the best war reporting ever written, but it should be read as it was written--one piece at a time, with plenty of time between each dispatch to let it settle.

One of the least well-known of the Vietnam books which stand out from the rest is a collection of short stories by Tom Mayer, called The Weary Falcon. Mayer graduated from Wallace Stegner's Stanford Writing Program, which also graduated such accomplished (and collected) writers as Larry McMurtry, Ken Kesey, Wendell Berry, Robert Stone, Tillie Olsen and many others. Mayer had written an earlier collection of stories, Bubble Gum and Kipling, prior to going to Vietnam. In a scenario not altogether unfamiliar to most collectors of modern first editions, Mayer's first book turns up fairly often but his second is nearly impossible to find. Presumably, his publisher had high hopes for the first and was disappointed; that combined with the general level of antipathy toward the Vietnam war by the time the second was published (1971) must have resulted in an extremely small first printing. If there are better stories than these written about the war, no one has shown them to me; this is a book full of humor, cynicism, pain and sorrow--the main ingredients of war, it would seem.

These elements--a dark, sometimes black, humor along with an intensely personal experience of the pain and loss of war--infuse all of the best literature of the war. A number of novels of distinction focus primarily on combat and the grunt's experience of the war: Close Quarters, by Larry Heinemann, has been called by many the best novel of the war, and its dark humor rings with an authenticity which is undeniable. Heinemann may have changed the names, but you have no trouble believing that this is exactly what it was like. His second book, Paco's Story, about a badly crippled Vietnam vet, was a surprise winner of the National Book Award. Fields of Fire, by James Webb--an outspoken Marine combat veteran who later became Secretary of the Navy under President Reagan, only to resign in disgust at the political game-playing which came with the Washington desk job--is another of the outstanding combat novels which, among other things, indirectly addresses the "M.I.A." question in a forthright, effective manner. One of the earliest combat novels was The LBJ Brigade, its title a pun on the initials of both President Lyndon B. Johnson and the Long Binh Jail, where deserters and others who ran afoul of the military authorities were sent. The LBJ Brigade was published in 1966 by a small Los Angeles publisher, Apocalypse Books, which seems to have disappeared after this one title. It is a grim, harrowing story of one veteran's brutal education in survival in the Vietnamese jungle, and the war it portrays has no winners. While such themes were commonplace in the literature later in the war and after the war had ended, in 1966 such a negative picture and such a strong antiwar message were unusual, to say the least.

Among other combat novels of distinction are John Del Vecchio's The Thirteenth Valley, highly praised for its historical accuracy and one of the few bestsellers among Vietnam novels, Robert Roth's Sand in the Wind and Winston Groom's Better Times Than These, all of which are self-consciously "big" novels in the tradition of the grand novels of the Second World War, The Naked and the Dead and From Here to Eternity.

But perhaps more typical of Vietnam, and more unique to it,

are the relatively unsung novels which quickly passed from

notice but which touch a nerve and speak directly to the

experiences of the individuals for whom the war was, in one

fashion or another, a central element of their lives. No

Bugles, No Drums, by Charles Durden, is a hilarious black

comedy which seethes with a kind of cynical rage which, it is

easy to forget, was the lingua franca of those

days--the one meeting ground for people of all political stripes.

On Distant Ground and The Alleys of Eden by

Robert Olen Butler are two of the most eloquent on the matter

of the attachments that Americans could form to Vietnam and

the Vietnamese people. The former also deals tellingly with

the difficult questions of loyalty which the war engendered in

all those for whom the official "party line" was insufficient

rationale for putting their lives on the line, in other words

nearly everyone. For, more than any other war, Vietnam was an

individual experience, played out to the count of the 365-day

rotation, and loyalty to oneself, one's country, and one's

ideals often seemed to be three different things, practically

unrelated one to another, sometimes mutually exclusive. What

these books share is the implicit conviction that the

individual was the final arbiter of the validity of the

Vietnam war, his (or her) experience the crucible in which

final judgement would be forged. This one the individuals

were going to call--not the politicians, not the generals,

not even the historians.

days--the one meeting ground for people of all political stripes.

On Distant Ground and The Alleys of Eden by

Robert Olen Butler are two of the most eloquent on the matter

of the attachments that Americans could form to Vietnam and

the Vietnamese people. The former also deals tellingly with

the difficult questions of loyalty which the war engendered in

all those for whom the official "party line" was insufficient

rationale for putting their lives on the line, in other words

nearly everyone. For, more than any other war, Vietnam was an

individual experience, played out to the count of the 365-day

rotation, and loyalty to oneself, one's country, and one's

ideals often seemed to be three different things, practically

unrelated one to another, sometimes mutually exclusive. What

these books share is the implicit conviction that the

individual was the final arbiter of the validity of the

Vietnam war, his (or her) experience the crucible in which

final judgement would be forged. This one the individuals

were going to call--not the politicians, not the generals,

not even the historians.

The predecessor of all Vietnam war novels is Graham Greene's The Quiet American, a light "entertainment," as he used to call them, which is partly based on a series of incidents in South Vietnam after the defeat of the French there involving U.S. intelligence agent Colonel Edward Lansdale, the CIA operative who has been called "the attending physician at the birth of South Vietnam." Another, more popular novel was also based on Lansdale--The Ugly American--although from a vastly different perspective. Greene's short and simple novel focuses on the theme of Western innocence and arrogance, and good intentions gone awry, and in that he succinctly anticipated the failure of the half-hearted and conflicted American efforts in Vietnam to a degree even he probably did not expect. Greene probably thought he was sketching, or caricaturing, the American involvement in Southeast Asia; few in 1956 would have guessed that his book would seem, in retrospect, to be a distillation of it.

Surprisingly, The Ugly American, one of the most commonly encountered of the early Vietnam-related titles, is one of the scarcest in the first printing. The book was a huge bestseller and most copies one finds are later printings. Complicating matters further, it was a Book-of-the-Month Club selection and book club editions abound. And finally, to further obscure the matter, some BOMC editions are printed from first edition sheets, and baldly state "First Edition" on the copyright page. The distinguishing features of the true first and the BOMC "first" are that the latter has the book club's usual blind stamp (a small circle, in this case) in the lower right corner of the rear cover; the true first also has an identifiable "point" on the dust jacket lacking on BOMC editions: the "blurb" on the front flap is attributed to author "John T. [sic] Marquand;" elsewhere, he is correctly identified as "John P. Marquand."

Another early title which is extremely scarce in the first edition despite being common in later printings is Robin Moore's The Green Berets. More than any other book, this one exemplifies both the early, heroic image of the U.S. fighting man in southeast Asia, while laying the groundwork for the later widespread understanding of the failure of the "allied" effort there: Moore's book made no bones about the inefficiencies and corruption of Saigon's government and the incompetence and downright treachery of its military--themes which were played out in many a left-leaning, more liberal book in later years. Moore, however, took something of a rightist stance, and contrasted the corrupt and cowardly Vietnamese to the valorous and morally upright U.S. Special Forces--the living embodiment of John F. Kennedy's idealistic notions of projecting democracy around the world. Nonetheless, the U.S. government objected strenuously to Moore's characterizations of its allies and tried to suppress the book. When the publisher would not buckle under to pressure to pull the book, a compromise was reached: a wraparound band was added to remaining copies of the first printing and copies of the later printings in stock at the time which declared in uppercase bold type: "FICTION STRANGER THAN FACT!" Small print extolled the book as an adventure novel, but the message was clear--this book was fiction, not fact; don't believe it. However, the very first lines of the book read: "The Green Berets is a book of truth," and the author goes on to claim veracity for the incidents described, if not absolute accuracy with regard to names and details. That such a "conservative" book, with such mild criticism of the war (at least by later standards), should have been objected to by the government is a telling fact, and revealing of just how far the country traveled down the path of skepticism in the next decade. For a collector, the ephemeral wraparound band is an added plus, even though it indicates a later "state" of the first edition.

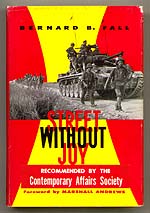

Some of the better literature of the war is unambiguously

nonfiction: Gloria Emerson's Winners and Losers, which

won the National Book Award, is a collection of pieces by an

award-winning correspondent for the New York Times

which gives voice to the Vietnamese views of the war as well

as American ones. Bernard Fall, the French reporter/historian

who was killed on patrol with U.S. Marines in 1967, wrote

several classic studies of the war--most notably Street

Without Joy, a prophetic study of the failure of the

French involvement in Vietnam, and Hell in a Very Small

Place, the definitive account of the pivotal siege of Dien

Bien Phu in 1954, the loss of which signalled the death of

French colonial hegemony in southeast Asia. A Bright

Shining Lie, by Neil Sheehan, won the Pulitzer Prize and

the National Book Award, and is history/biography as

compelling as any fiction and a good deal more improbable at

times than fiction would dare to be. 365 Days, by

Ronald Glasser, a medical doctor stationed in Japan whose job

was to treat the casualties who were too severely wounded to

be treated "in-country," is a moving collection of his

patients' stories which reminds one that most of the burden of

fighting this war fell on teenagers--kids who may have gone

through boot camp but lacked the life experience to make moral

sense of what was happening to them and what they were doing.

His stories of their unthinking courage and compassion are as

moving as the stories of atrocities are revolting. The

strands of history wove a complex and dark fabric in the wars

in southeast Asia and the best of these books convey with

great clarity a few of the individual threads while giving a

sense of the overall texture of the whole.

as American ones. Bernard Fall, the French reporter/historian

who was killed on patrol with U.S. Marines in 1967, wrote

several classic studies of the war--most notably Street

Without Joy, a prophetic study of the failure of the

French involvement in Vietnam, and Hell in a Very Small

Place, the definitive account of the pivotal siege of Dien

Bien Phu in 1954, the loss of which signalled the death of

French colonial hegemony in southeast Asia. A Bright

Shining Lie, by Neil Sheehan, won the Pulitzer Prize and

the National Book Award, and is history/biography as

compelling as any fiction and a good deal more improbable at

times than fiction would dare to be. 365 Days, by

Ronald Glasser, a medical doctor stationed in Japan whose job

was to treat the casualties who were too severely wounded to

be treated "in-country," is a moving collection of his

patients' stories which reminds one that most of the burden of

fighting this war fell on teenagers--kids who may have gone

through boot camp but lacked the life experience to make moral

sense of what was happening to them and what they were doing.

His stories of their unthinking courage and compassion are as

moving as the stories of atrocities are revolting. The

strands of history wove a complex and dark fabric in the wars

in southeast Asia and the best of these books convey with

great clarity a few of the individual threads while giving a

sense of the overall texture of the whole.

The question of fact or fiction, however, hangs over many Vietnam books like a cloud: the publisher of If I Die in a Combat Zone categorized the book as fiction in one edition, nonfiction in another. Such novels as Heinemann's Close Quarters, science fiction author Joe Haldeman's first book, War Year, Kent Anderson's excellent novel Sympathy for the Devil and a host of others seem to be clearly drawn from the authors' own experiences: it is easy to imagine that many of the Vietnam novels are simply memoirs with the names changed. But the nonfiction is similar: O'Brien's Combat Zone explicitly acknowledges changing characters' names and telescoping events--in other words using fictional techniques and conventions in a purportedly nonfiction book. Other nonfiction accounts do the same and Philip Caputo's ground-breaking and bestselling memoir A Rumor of War and Ron Kovic's bestselling Born on the Fourth of July, one of the first Vietnam memoirs to reach a wide reading public and later the basis for the Oliver Stone film, both read like novels.

It is not surprising and is somehow fitting therefore that a book which may well come to be considered by future generations to be the "best" book to come out of the war begs all of the usual questions: is it fiction or nonfiction? A free-form novel, a collection of stories, or a collection of personal accounts? None of the above? Some combination of all of the above? Tim O'Brien's fifth book, The Things They Carried, is a collection of related vignettes with a main character named "Tim O'Brien" whose biography, such as we come to know it, bears strong resemblances to the author's own. It is a book worthy of comparison to Stephen Crane's Civil War classic The Red Badge of Courage: that is, it is a simple tale told from the perspective of one foot soldier, that rings with authenticity and universality and is all the more powerful for the book's apparently not pretending to much more than a simple recounting. O'Brien's prose is direct and the war and his characters' experiences of it come across with an immediacy which is almost scary. If this isn't exactly what they felt, then it is better: it is the essence of what they felt. The whole tale is couched in a series of reflections on stories and storytelling and the relation they bear to truth which provides a clue to the context in which this book should be understood: O'Brien is not only writing for a contemporary audience but he is also writing for all those to come who will only have the story to go by, not this generation's experience.

Vietnam is still a hard subject to explore; the arguments and feelings which cut so deep left behind a psychic scar. We feel as if we've heard it all before, there's nothing new, they are all futile, dead issues. But the best of the books are remarkably free of trite and cliched polemics, and reveal a wound on the American soul which, if exposed to the air, has a chance to heal; if hidden away, it can only fester.

Copyright © 1992 by Ken Lopez